1968 - 1978

The late 1960s were a time of social and political unrest. As anti-war and civil rights protests swept the country, Native American leaders launched a movement to restore tribal sovereignty, which had been eroding for decades under the U.S. government’s “termination policies.” In the early 1970s, the Pine Ridge Reservation became the epicenter of the fight for self-determination when American Indian Movement activists occupied the site of the Wounded Knee Massacre to demand the United States begin honoring its broken treaties with the tribes.

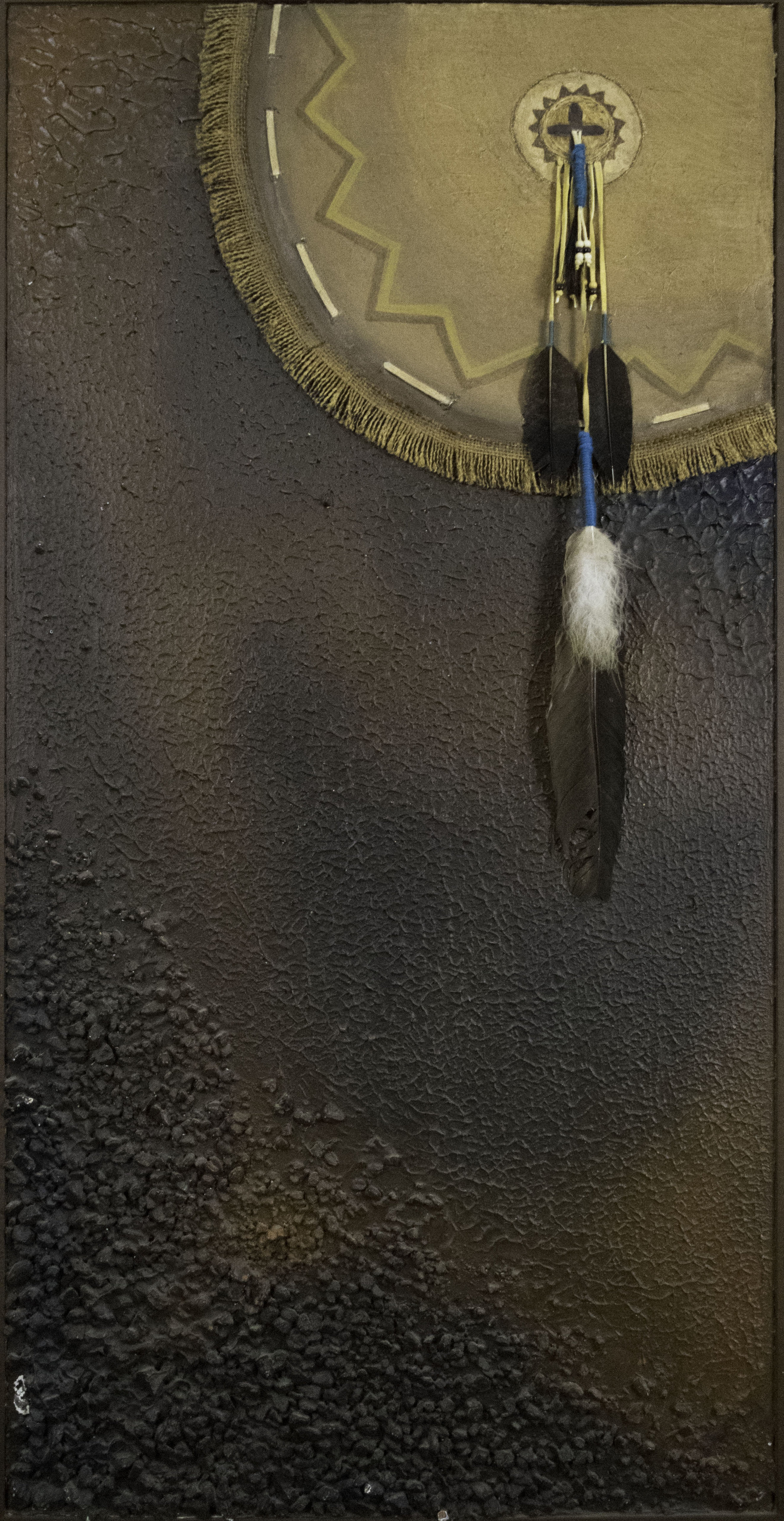

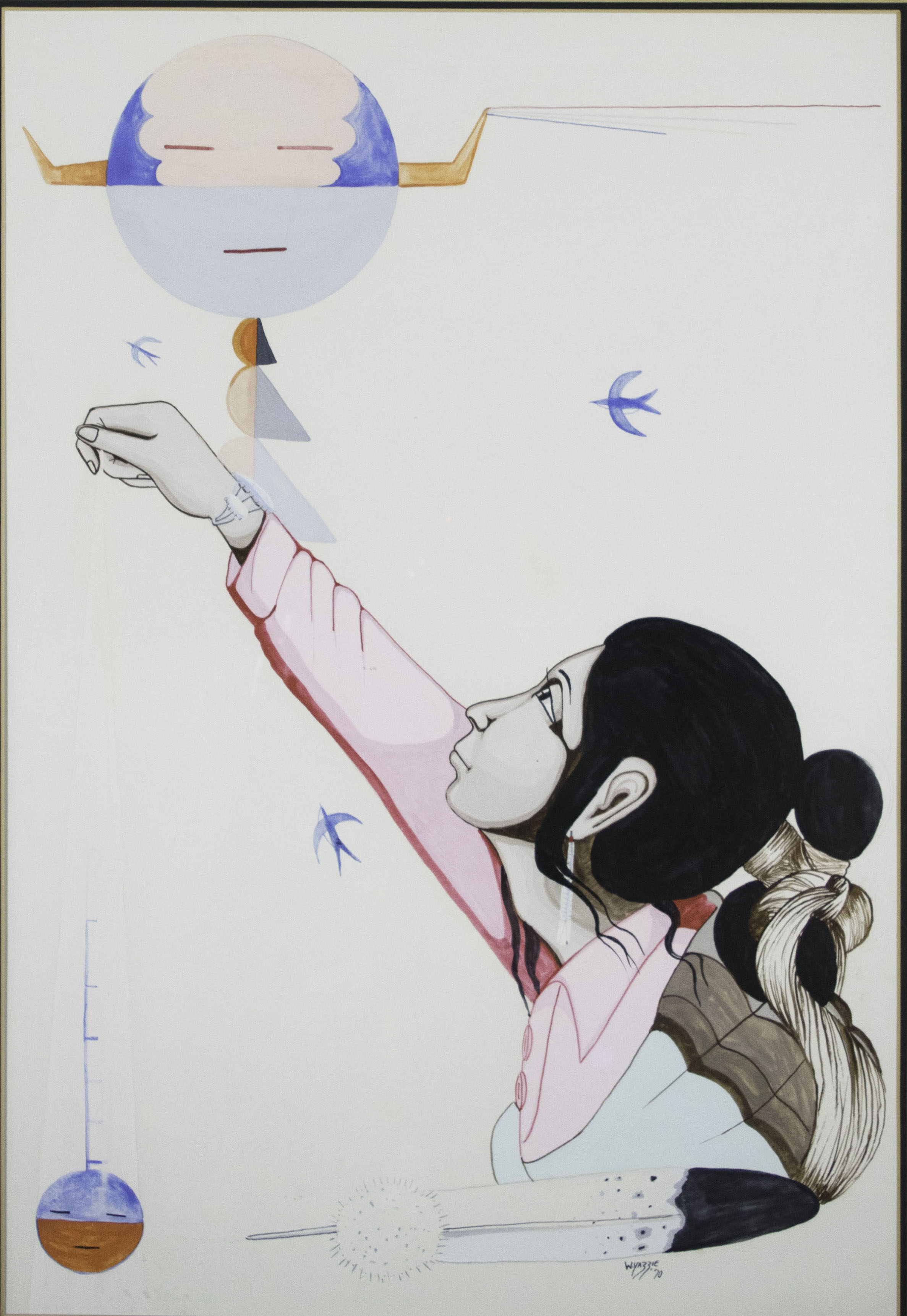

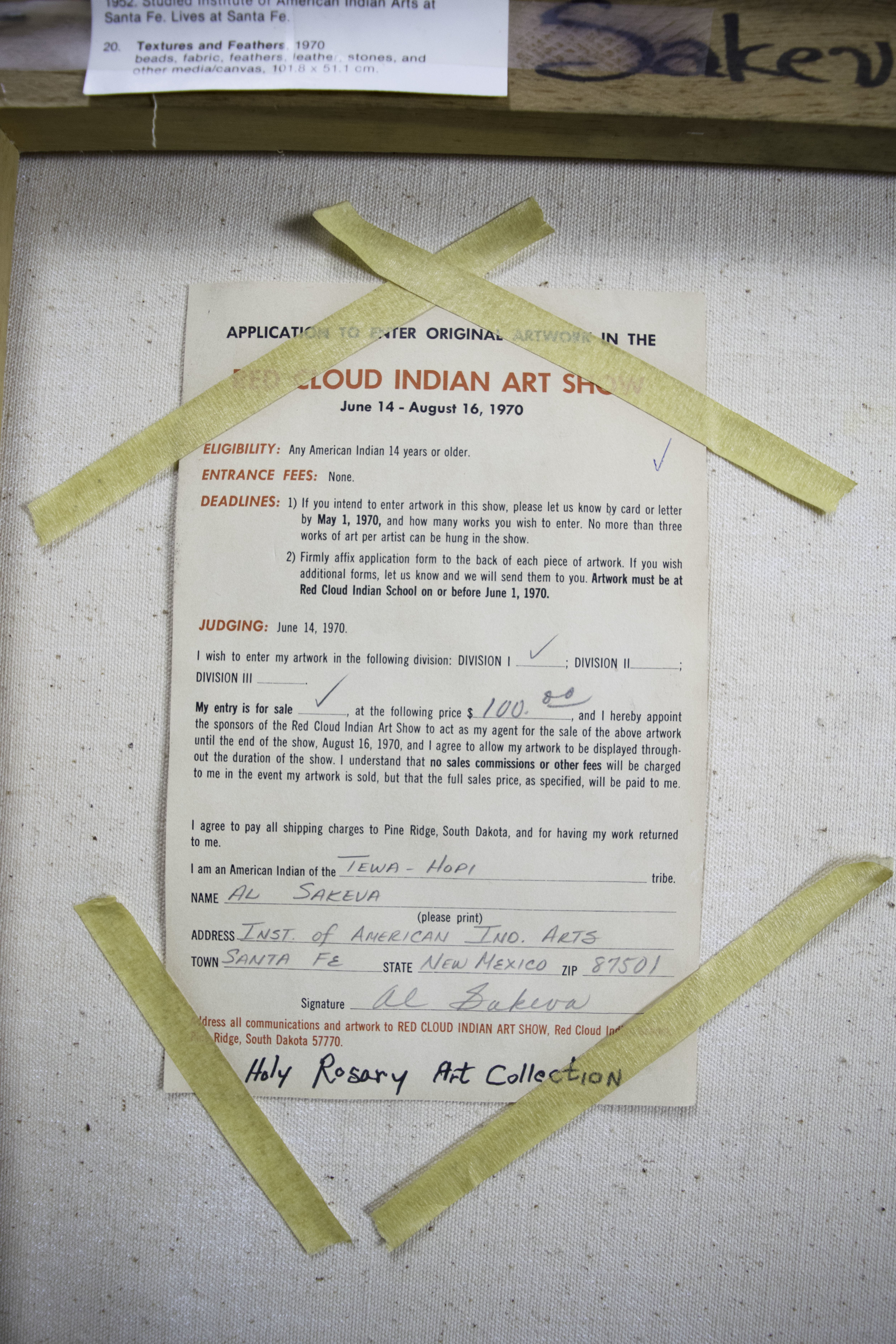

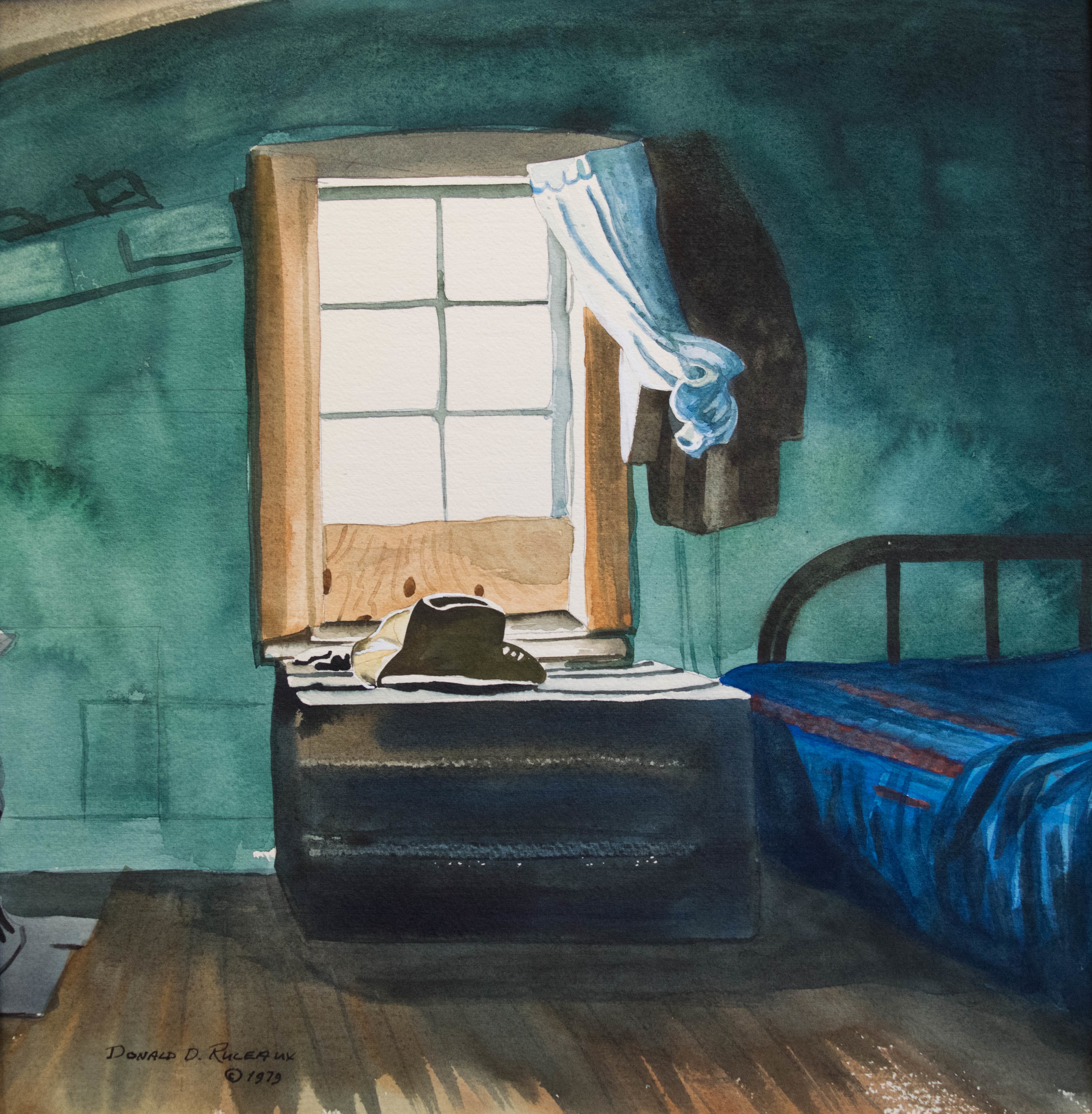

On campus, Jesuit Theodore “Ted” Zuern (1921–2007) became president of Red Cloud in 1968. As an educator, Father Ted had long recognized the need to further integrate Lakota culture, language, and art into campus life—an instinct which led him to collaborate with Robert “Bob” Savage to organize the inaugural Art Show. That first show was modest and informal—but it accomplished something groundbreaking. By allowing “any American Indian 14 years or older” to enter, it encouraged young artists just beginning their careers to share their artistic vision alongside more seasoned and professional artists. Red Cloud’s campus bookkeeper, the incomparable Brother C.M. Simon, S.J., took on the task of managing future Art Shows, a role he would hold for decades to come.

DECADE TWO

1978 - 1988

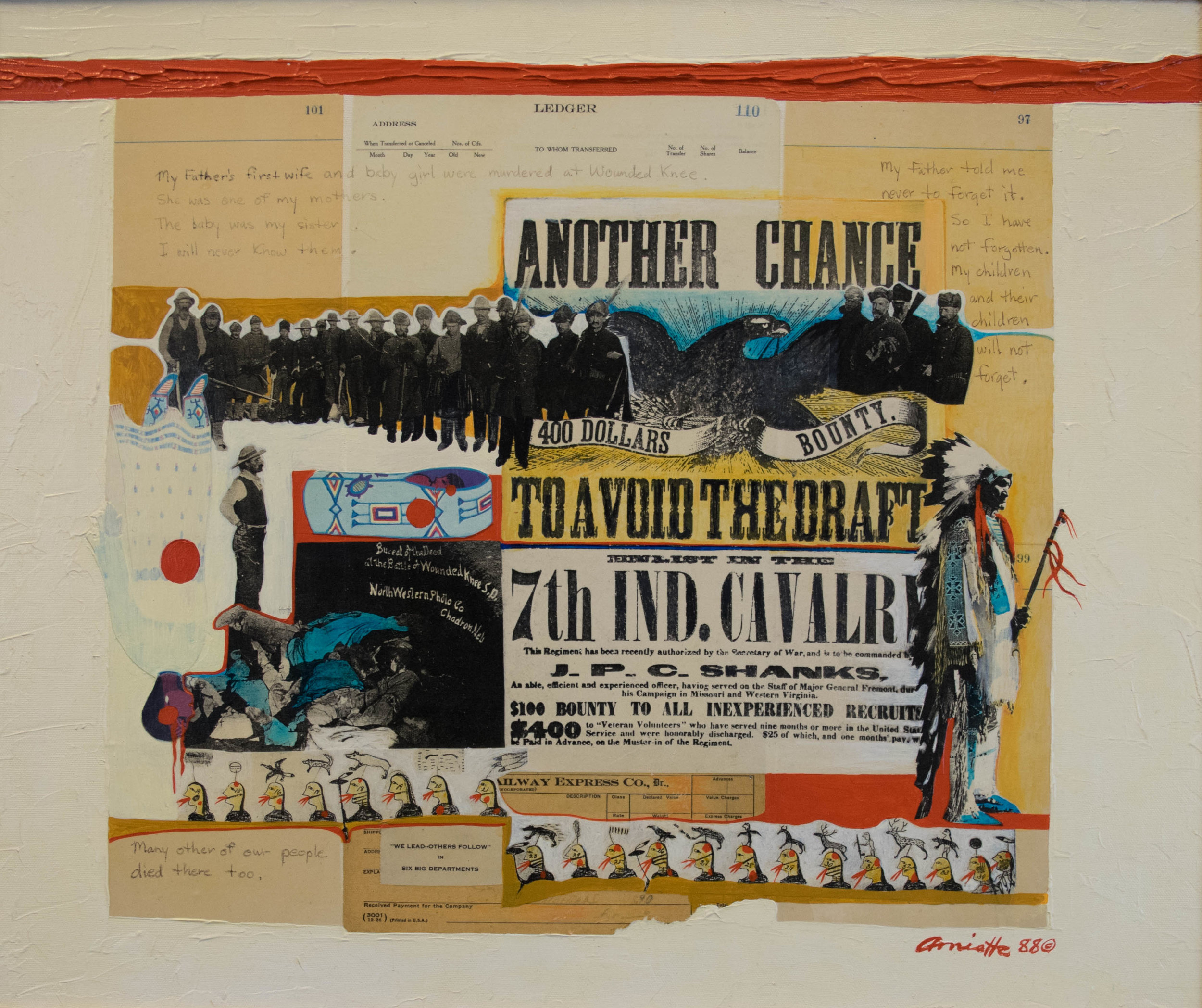

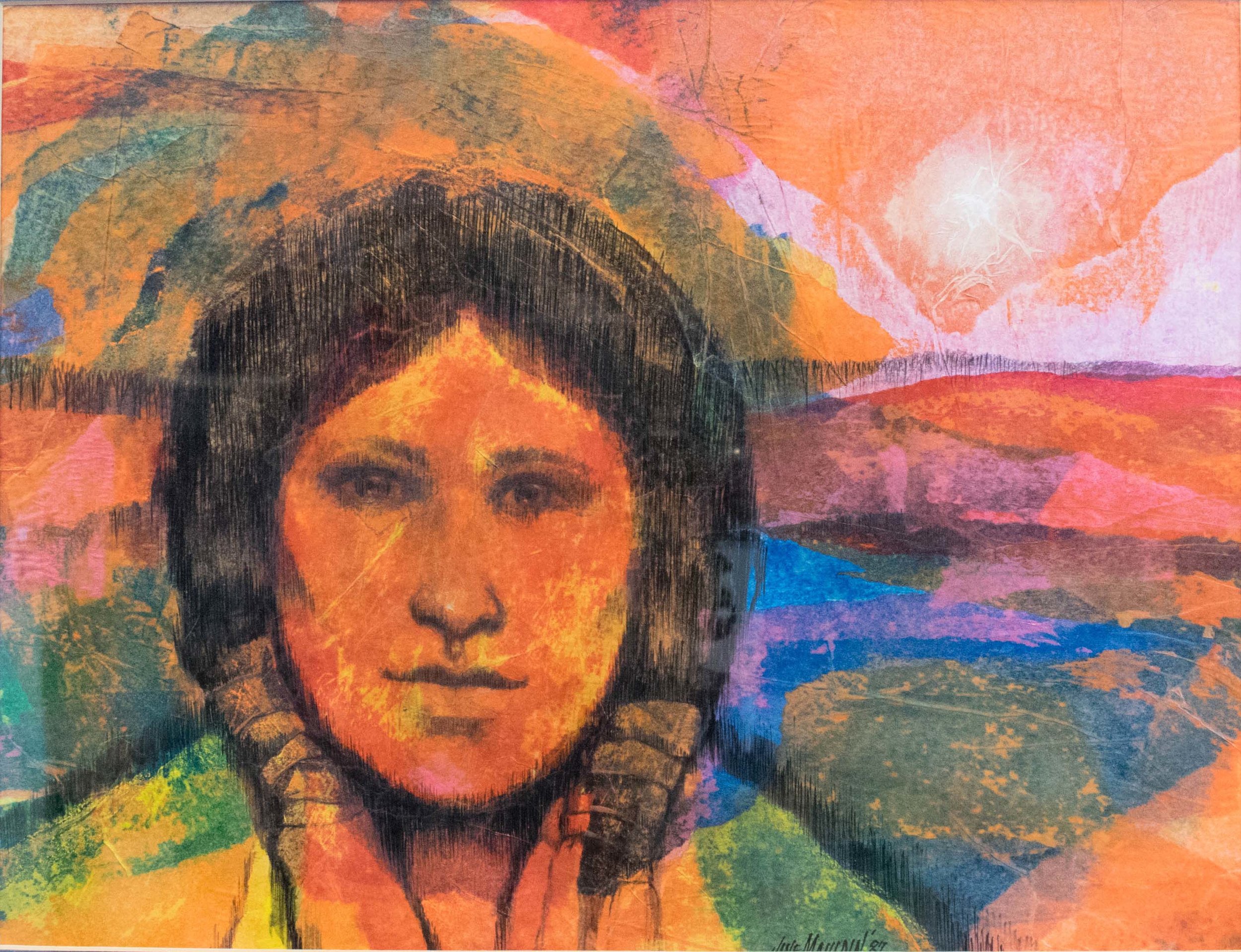

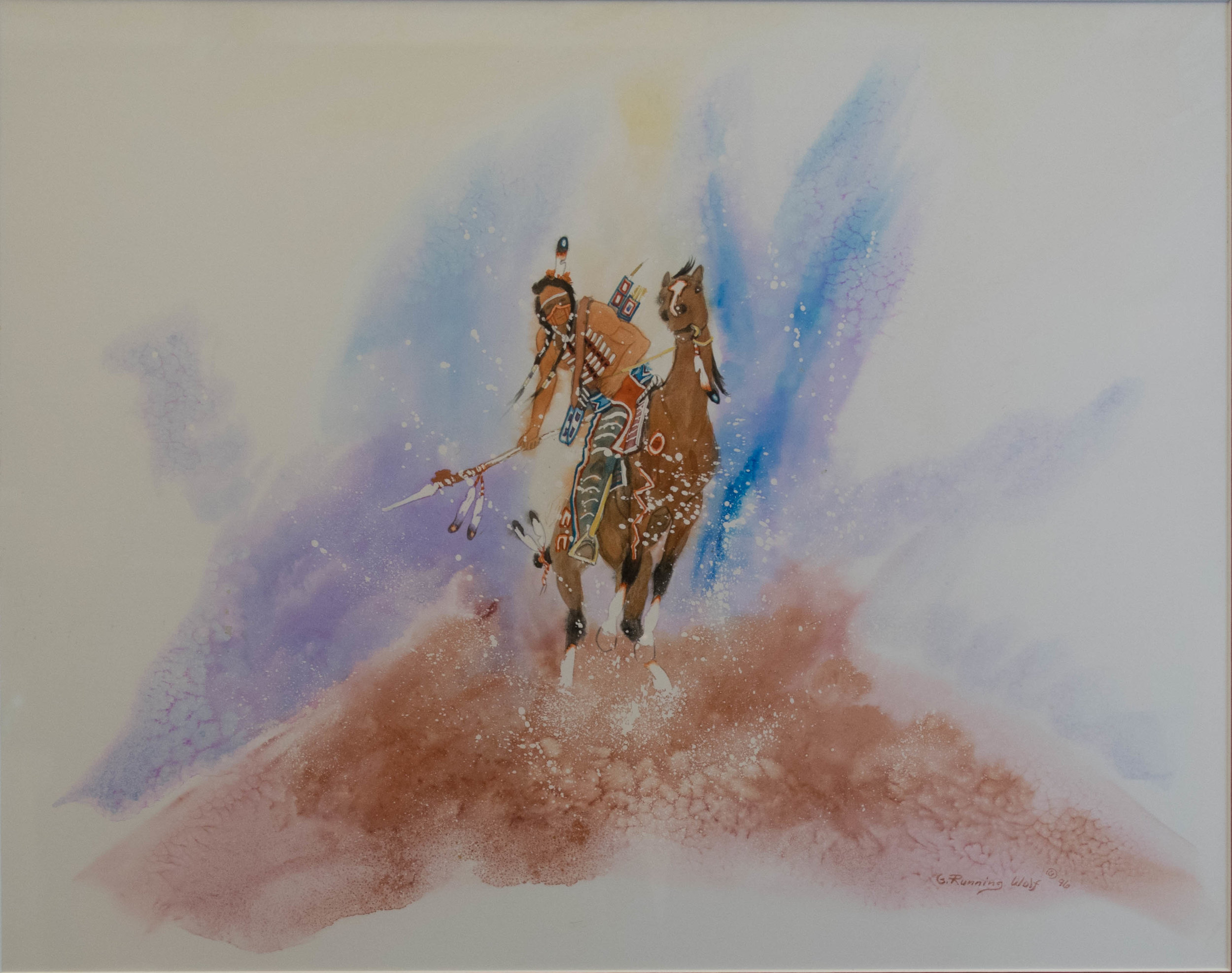

Oglala Lakota artists emerged as a powerful force in the Native art world during the show’s second decade. In 1983, a number of Lakota artists created the Dreamcatchers Artist Guild to set standards for authenticating Lakota art, to create markets for Lakota artists to promote and sell their work, and to educate the public about Lakota culture. At the same time, many of the Red Cloud show’s earliest contributors, including Donald Montileaux, Mary Morez, Arthur Amiotte, and Dan Namingha, went on to become some of the nation’s most prominent Native artists.

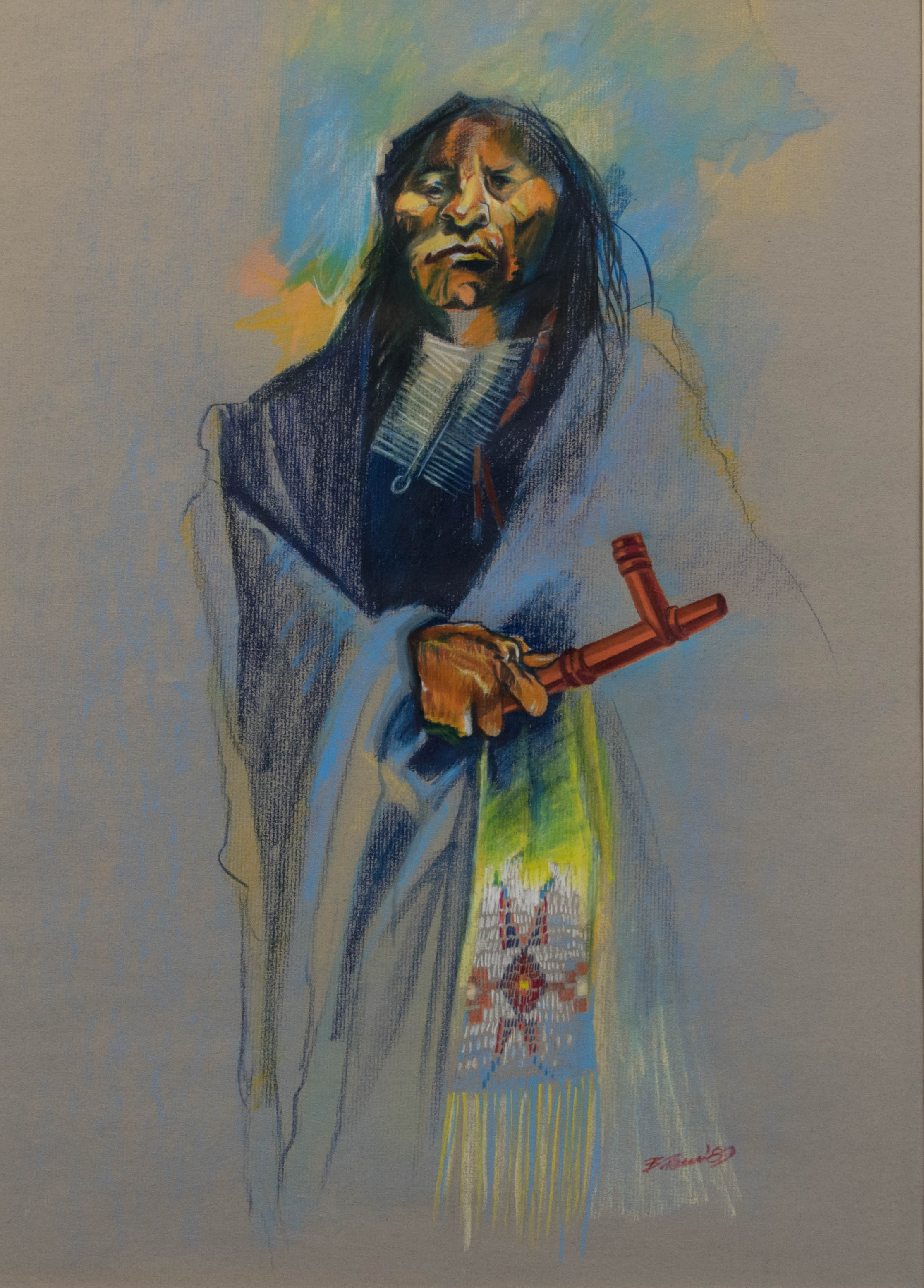

On Red Cloud’s campus, Brother Simon continued to manage the show’s growth, working tirelessly to promote Lakota and other Native art. Instantly recognizable with his traditional black robes, beard, and pipe, Brother Simon developed strong bonds with local Lakota artists and continued to purchase and sell their work on campus, creating a much needed source of income for the reservation. Ultimately, he amassed an extensive collection of paintings, drawings, and sculptures by Lakota and other diverse Native artists. As the need for dedicated space became clear, plans for The Heritage Center began to take shape. Its gallery doors finally swung open in 1982, just in time for the 14th Red Cloud Indian Art Show.

DECADE THREE

1988 - 1998

A national movement to honor the contributions of indigenous Americans and to restore historical artifacts to the tribes took hold. In 1989, Congress passed the National Museum of the American Indian Act to create a new Smithsonian Museum on the National Mall—to serve as “a living memorial to Native Americans and their traditions.” The following year, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, or NAGPRA, began requiring federal agencies to return sacred objects to the tribes that created them.

Within that movement, The Heritage Center expanded its efforts to celebrate living Native artists. Brother Simon helped to establish the Northern Plains Indian Arts Market—now the largest art market promoting the work of Northern Plains tribes. He also contributed to the publication of what he called his “bible,” The Biographical Directory of Native American Painters. And, in partnership with the University of South Dakota Art Department Chair John A. Day, a number of influential exhibits featuring regional Native artists were created, traveled, and cataloged.

On campus, The Heritage Center’s gift shop grew as Brother Simon purchased and sold beadwork, quillwork, parfleche, and more to spur economic opportunities for the artist community on the reservation. Although a devastating 1996 fire forced The Heritage Center to close its gallery space for two years, the Red Cloud Indian Art Show continued to grow and attract new artists.

DECADE FOUR

1998 - 2008

Understanding the diversity of tribal culture and art through cutting-edge research became a clear focus, nationally and locally. Just outside Washington, DC, the Cultural Resources Center, part of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI), opened in 1999 to support “…proper conservation, protection, handling, cataloging, research, and study of the museum's collections.” Five years later, NMAI’s flagship building opened at the National Mall.

In 2003, The Heritage Center launched its own efforts to research and catalog its growing permanent collection. Mary V. Bordeaux (Sicangu Lakota), a museum studies graduate of the Institute of American Indian Arts, was hired to manage the work of identifying, tracing, and studying the collection’s estimated 3,000 pieces of artwork. Director Peter Strong came on board in 2005. The cataloging process, which employed as many as twenty-three interns at one time, was largely completed in 2009, and the team revealed The Heritage Center actually held closer to 10,000 pieces.

Brother Simon, who had led the development of the Art Show and The Heritage Center programs for almost four decades, unexpectedly passed away in 2006. Bordeaux stepped into the role of curator, with an aim to protect and grow his legacy and to help The Heritage Center grow into a hub of forward-looking Native art and creativity.

DECADE FIVE

2008 - 2018

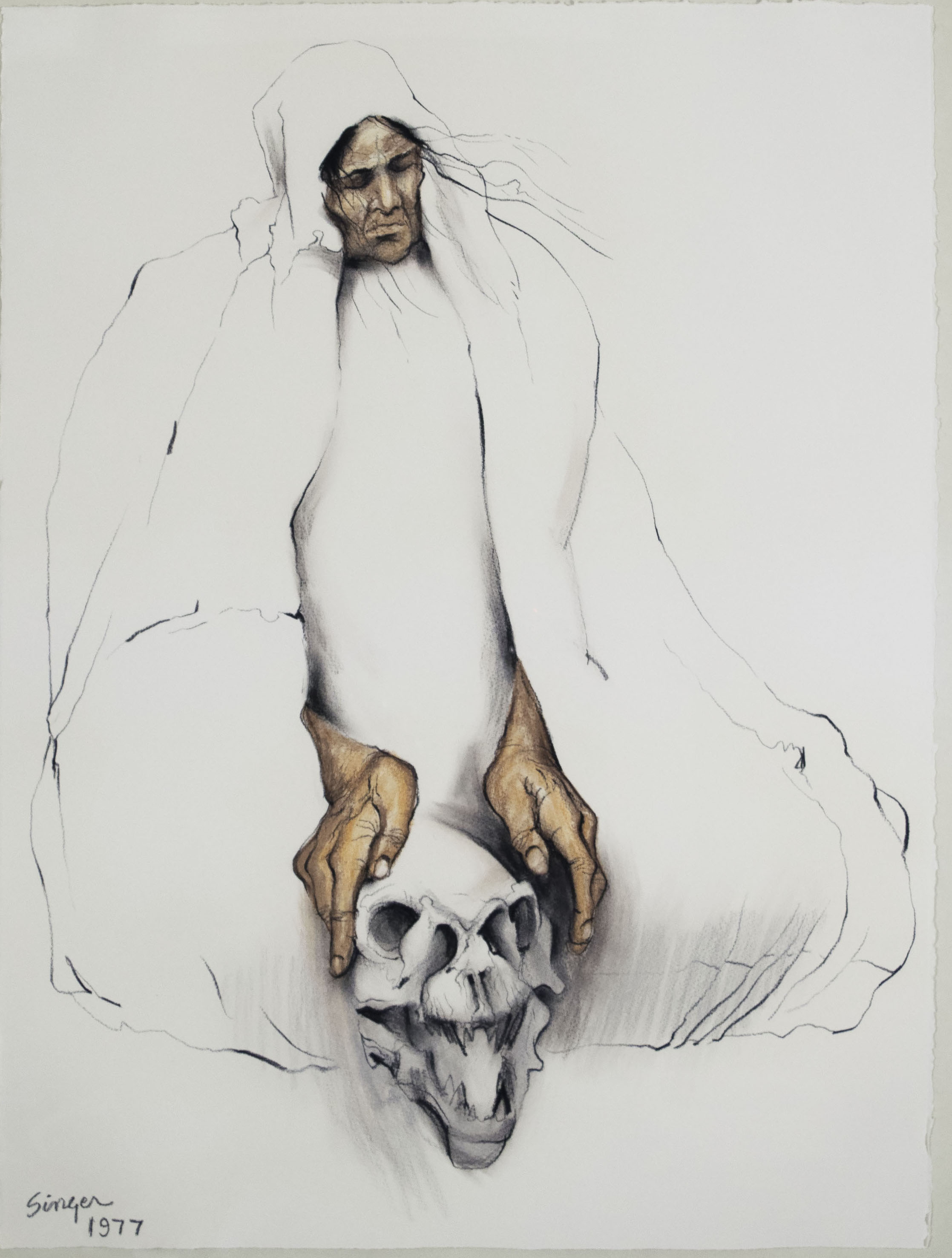

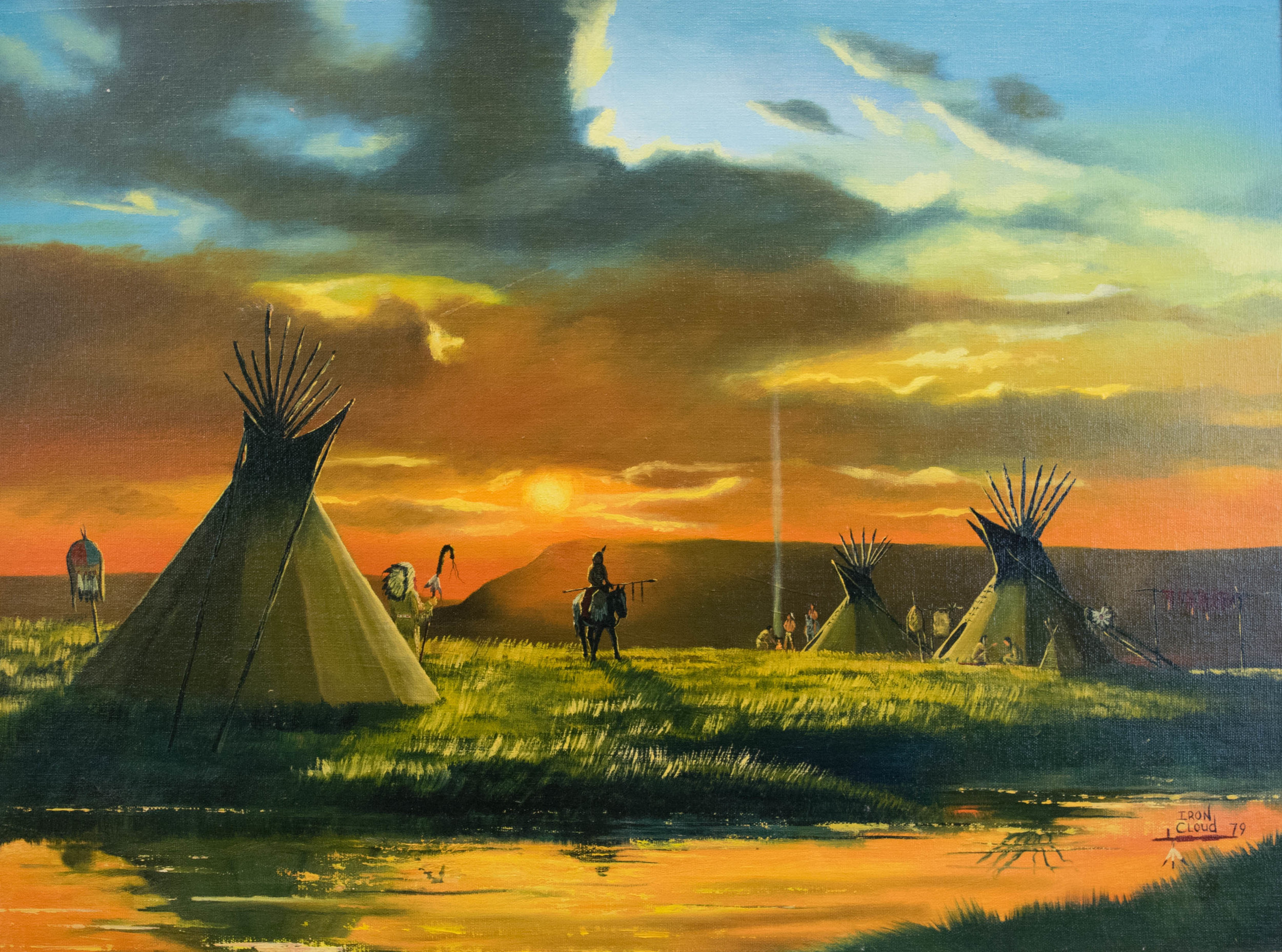

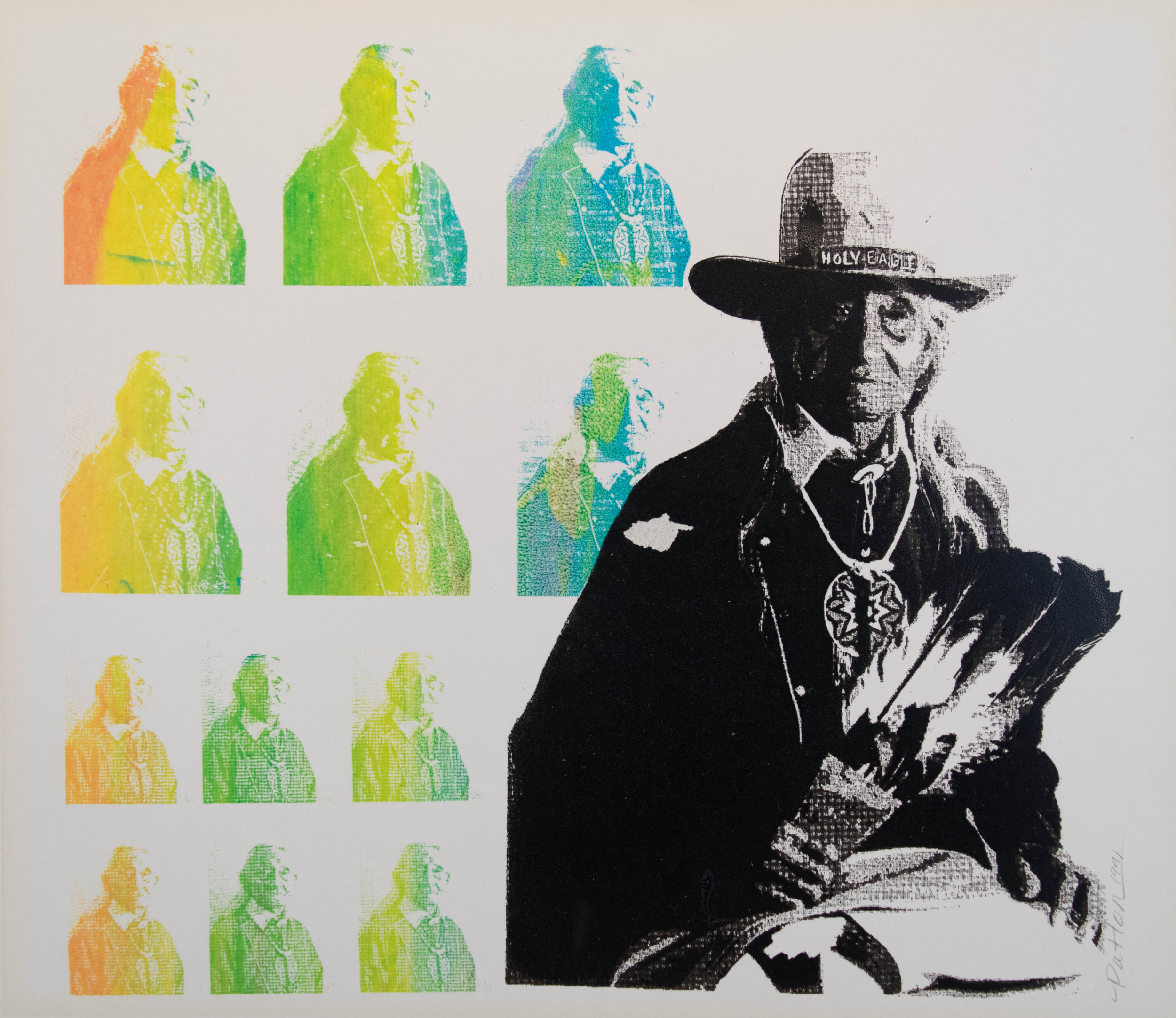

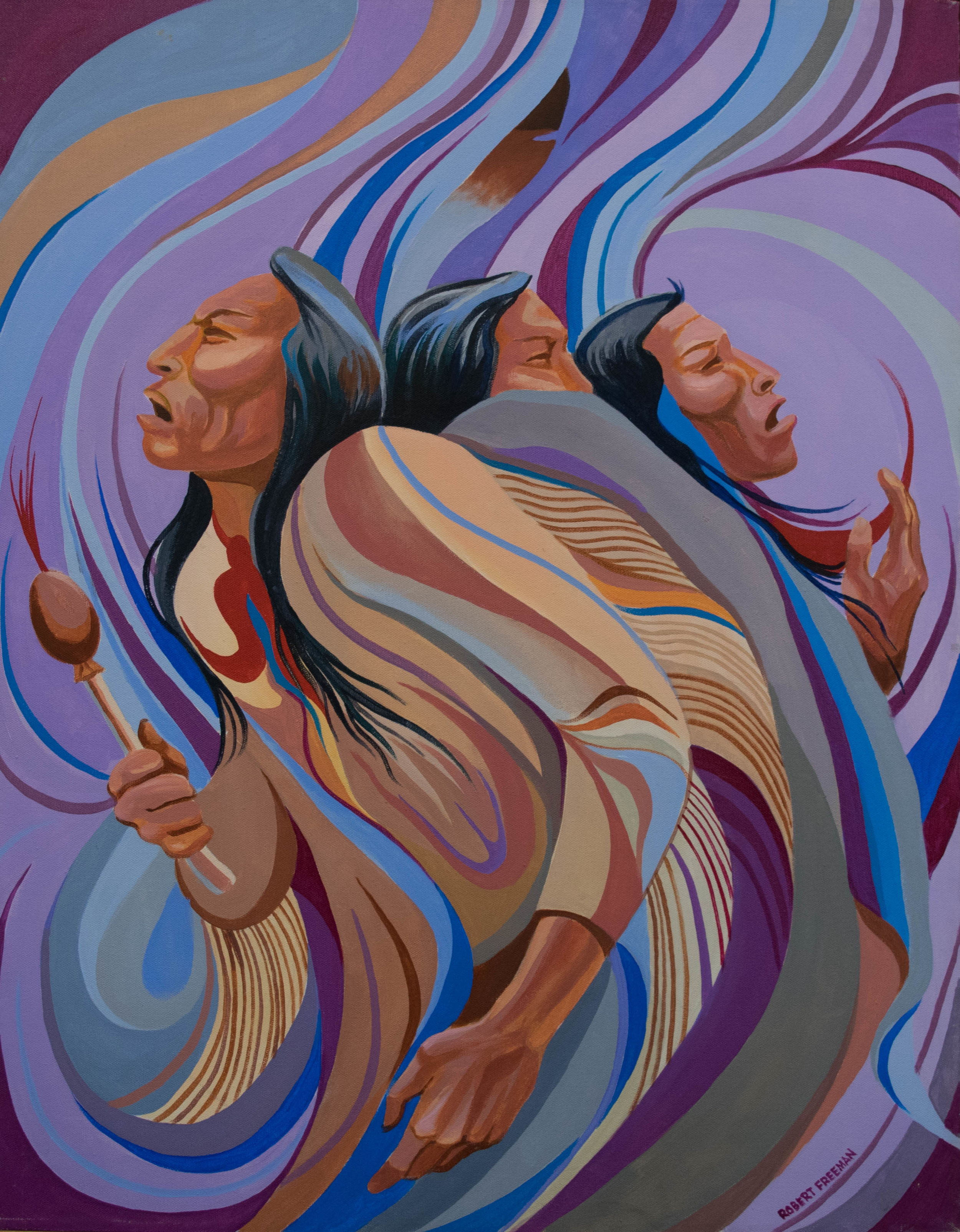

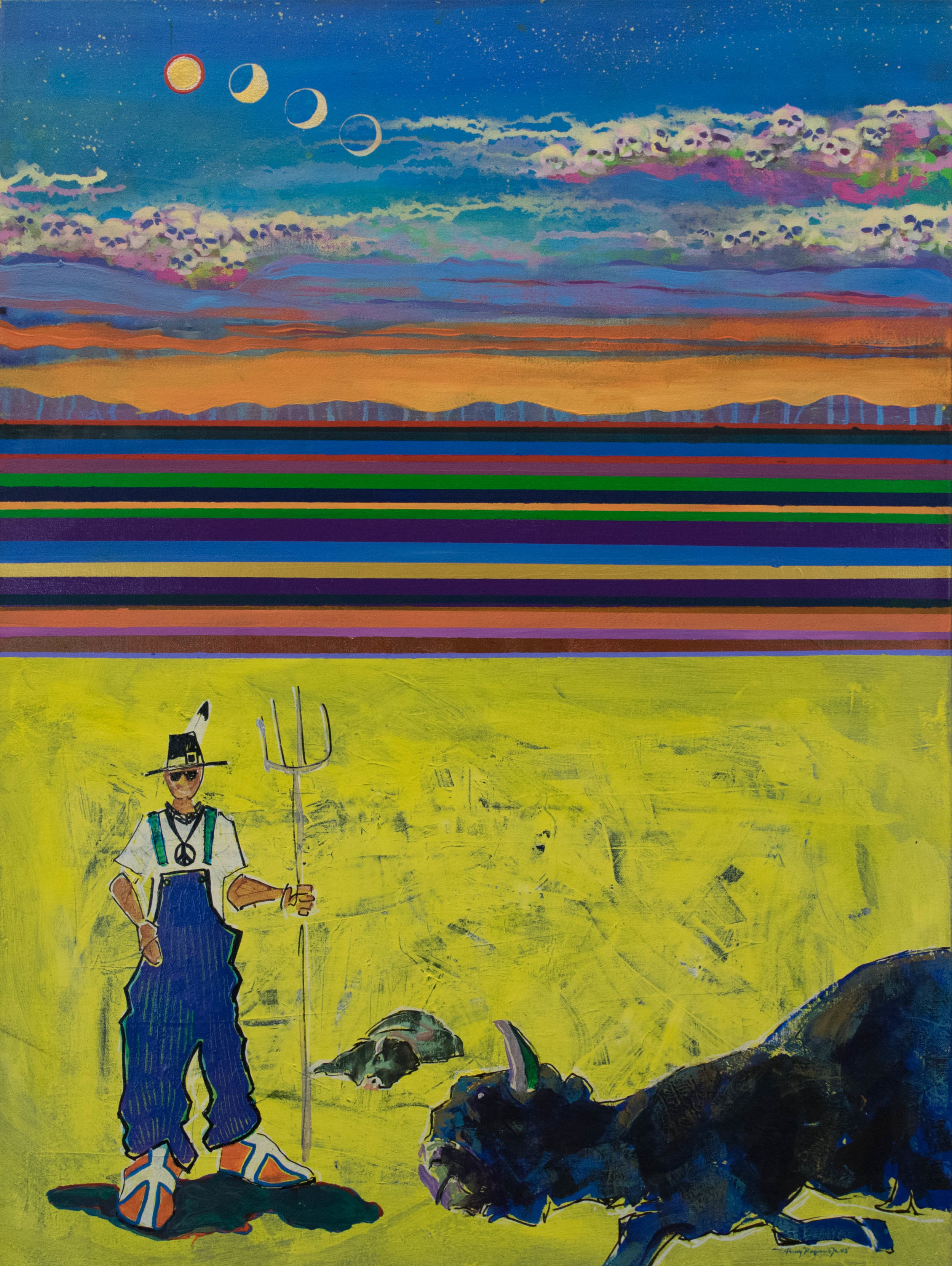

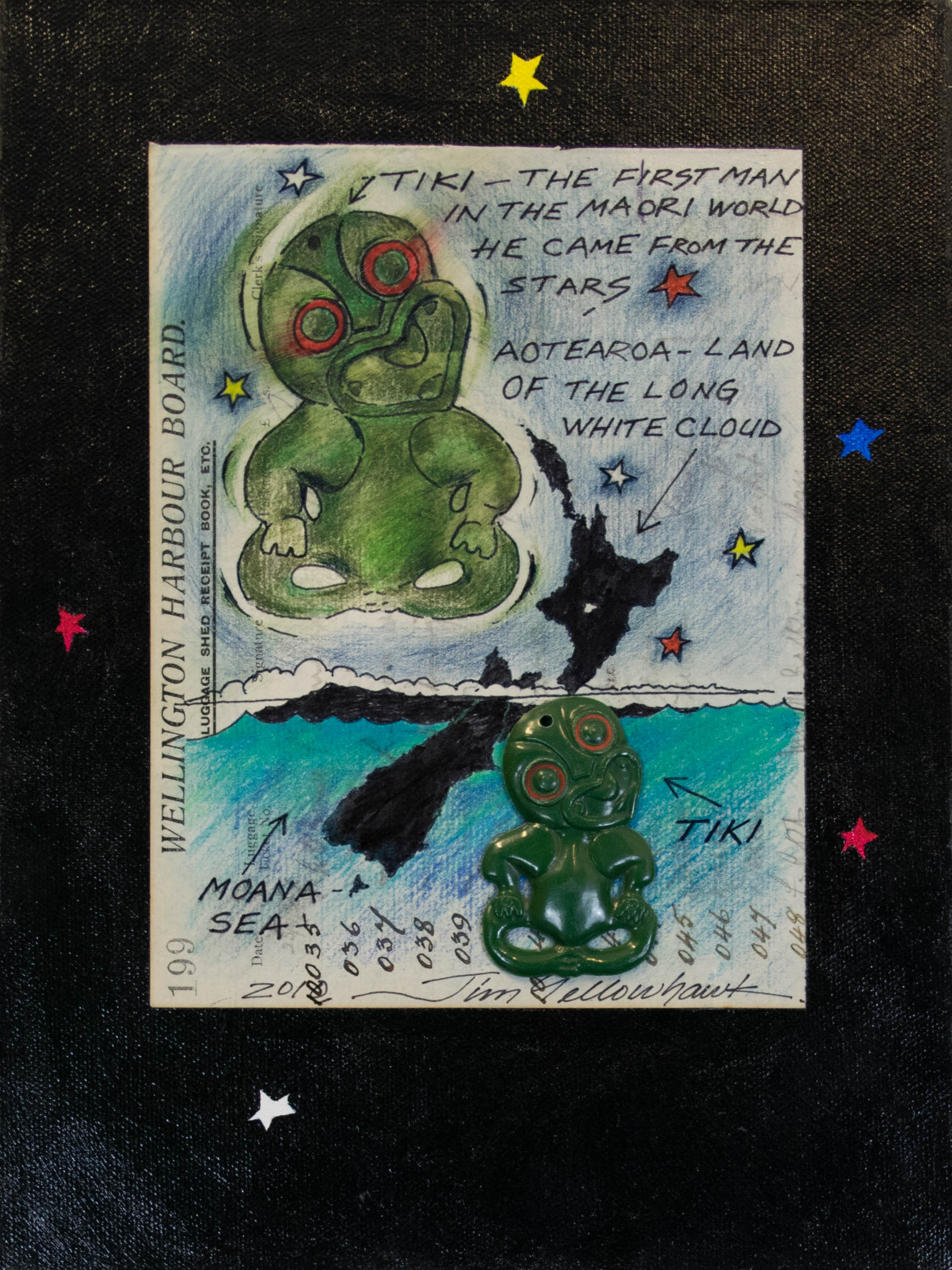

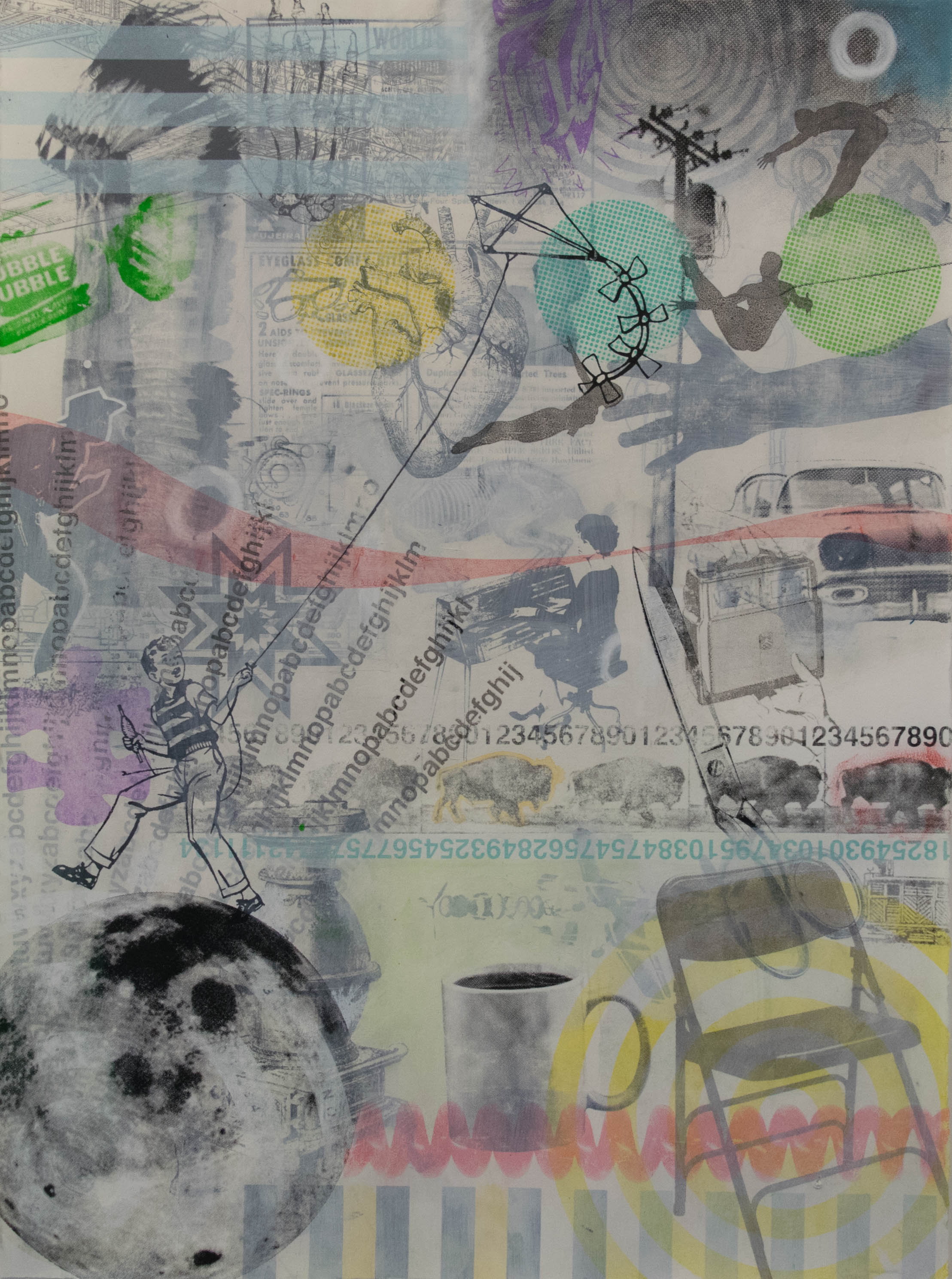

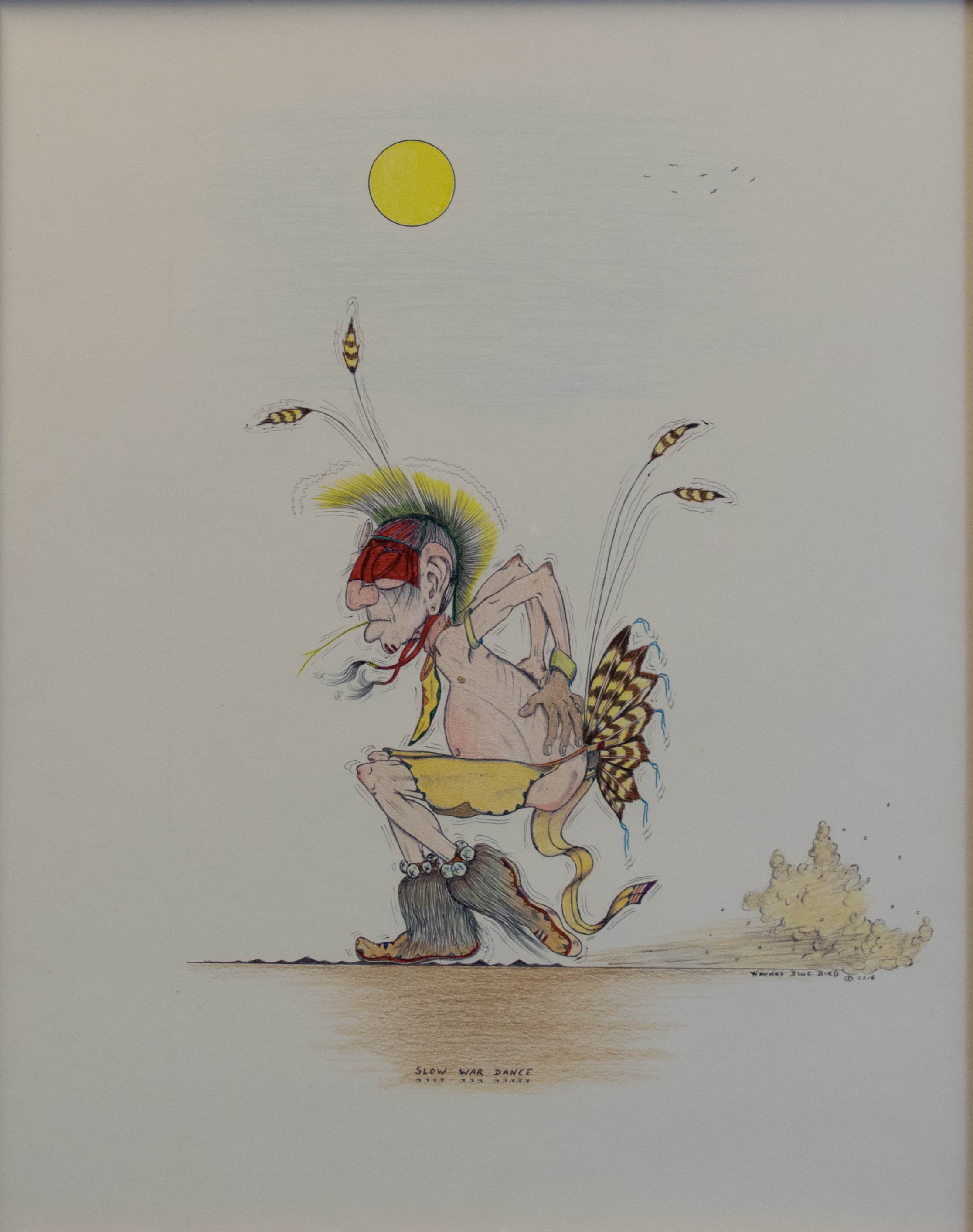

Romanticized images of Native American life expanded and evolved as Native artists addressed the complex social, cultural, and political realities facing indigenous communities through their work. With that evolution, they finally began to find recognition in the world of fine art. Native artists and arts professionals led the way for galleries and museums across the country and around the world to feature contemporary works exploring the experiences of Native artists and Native peoples.

In the midst of that work, the Red Cloud Indian Art Show deepened its long-standing mission: to create opportunities for all Native artists to show their work and share their voice. By bringing new visitors to Pine Ridge, creating traveling exhibitions for galleries and museums, and developing cutting-edge arts education programs, it allows new audiences to experience the power of Lakota and other Native art. And with each passing decade, through the Red Cloud Indian Art Show, it continues to celebrate each new generation of Native artists and gives them a platform to share their work with the world.